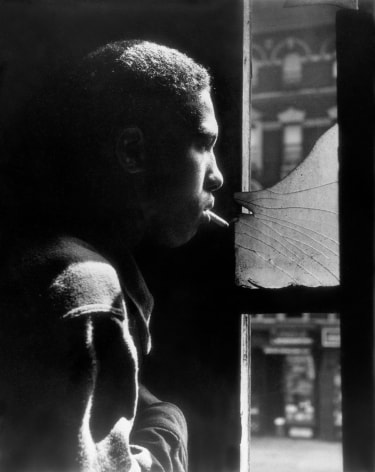

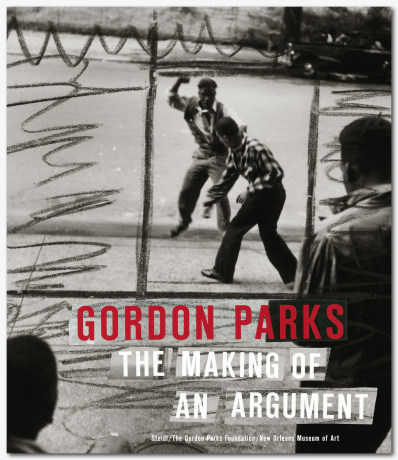

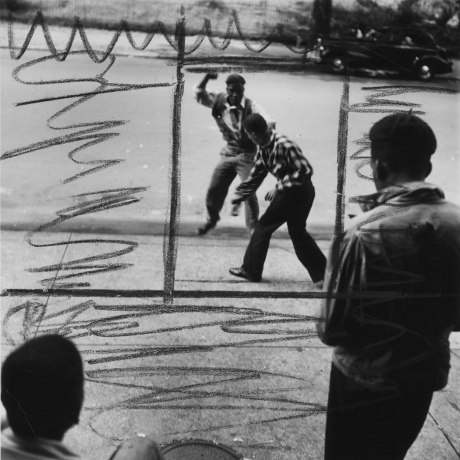

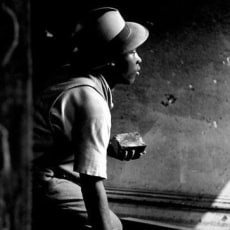

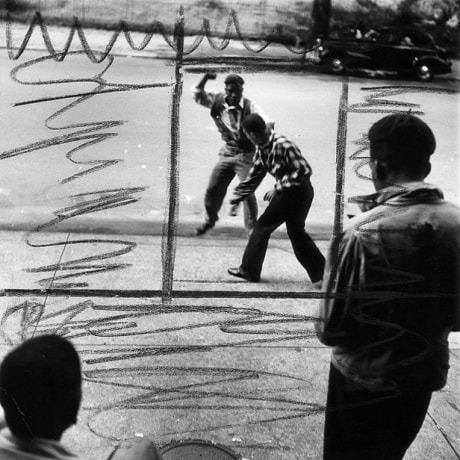

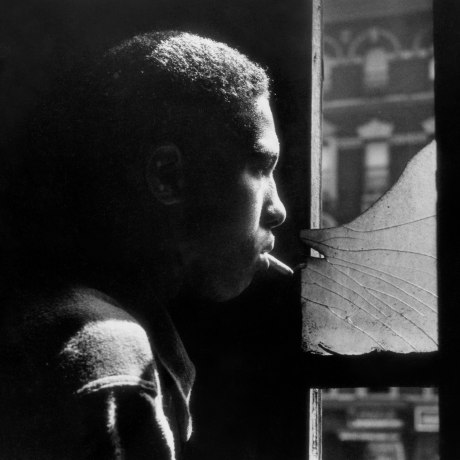

An intent young man holds a brick, waiting for something to happen. Kids play in the spray of a fire hydrant. Two young men fight, fists in the air, while others look on. These images of Harlem in 1948 were the result of African-American photographer Gordon Parks entering the inner circle of a teenaged gang leader, Leonard “Red” Jackson. Parks spent a month with Jackson, accompanying him to fights, diplomatic sessions with other gangs, quiet moments at home, and even the wake of another gang member. The outcome was a photo essay, “Harlem Gang Leader,” published in Life that same year, which helped to establish Parks as one of America’s most significant social photographers of the 20th century.

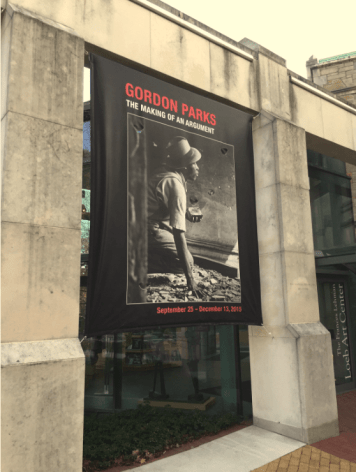

The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center’s special exhibition, Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument, takes a behind-the-scenes look at the editorial decisions leading up to the publication of this photo essay. The show opens September 25 and will be on view through December 13.

Comprised of vintage photographs, original issues of Life magazine, contact sheets and proof prints, The Making of an Argument traces the editorial process and parses out the various voices and motives behind the production of the picture essay, raising important questions about photography as a documentary tool and a narrative device, its role in addressing social concerns, and its function in the world of publishing.

The publication of “Harlem Gang Leader” was a watershed moment, leading to Life offering Parks a job and making him the first (and, for 20 years, the only) African-American photographer on the staff of a major American magazine or newspaper. Despite this, Parks was troubled by the photo essay. He felt that although the young gang leader Leonard “Red” Jackson did live in a world marked by fear and violence, the emphasis the magazine’s editors placed on these aspects of life in Harlem created a one-dimensional story.

Yet Parks also acknowledged that without the violence, Life might never have published the essay. Parks’ frustration was rooted in the tension between his hopes for the essay and the final product. He wanted to illustrate the conditions that fostered delinquency and teen gangs in African-American communities and encourage government and social service agencies to intervene. Life offered him the platform that he desired, but it came with a price: he had to cede control of the essay to the magazine’s editors.

Parks would remain at Life for two decades, chronicling subjects related to racism and poverty, as well as taking memorable pictures of celebrities and politicians (including Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and Stokely Carmichael). His most famous images, such as Emerging Man (1952) and American Gothic (1942) capture the essence of activism and humanitarianism in mid-20th century America and have become iconic images, defining their era for later generations. They also rallied support for the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, for which Parks himself was a tireless advocate as well as a documentarian.

“One of Parks’ greatest strengths was his unwavering trust in people,” says Peter Kunhardt, executive director of the Gordon Parks Foundation, which is in Pleasantville, New York. “This trust opened up doors for him to create intimate and profound portraits of his subjects, sometimes despite harsh conditions.”

Russell Lord, the Freeman Family Curator of Photographs at the New Orleans Museum of Art and the curator of the exhibition, notes that in the case of the “Harlem Gang Leader” pictures, “Parks’ presence became so familiar that at times he seems almost invisible, the lives (and deaths) of his protagonists unfolding before his camera as if it, and he, were not even there.” The photos prove it: Parks became a welcome companion at Jackson’s activities at home and in the streets.

Later in life, Parks evolved into a modern-day Renaissance man. The first African-American director to helm a major motion picture, he introduced the Blaxploitation genre through his film Shaft (1971). He wrote numerous memoirs, novels, and books of poetry. Parks received many awards, including the National Medal of the Arts and more than fifty honorary degrees. A humanitarian with a deep commitment to social justice, he left behind a body of work that documents many of the most important aspects of American culture from the early 1940s up until his death. Parks died at the age of 93 in 2006.

Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument was organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art, in collaboration with the Gordon Parks Foundation. Funding for the presentation at Vassar is provided by the Horace Goldsmith Exhibition Fund and the Friends of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center Exhibition Fund.

Over the last decade, photography has played a large part in the exhibition program at the Art Center with at least one exhibition dedicated to photography each year. In the recent past there have been one-person exhibitions of work by Emmet Gowin, Kunié Sugiura, Andreas Feininger, Eirik Johnson, and Malick Sidibé and several thematic group exhibitions which include The Polaroid Years: Instant Photography and Experimentation (2013); 150 Years Later: New Photography from Tina Barney, Tim Davis, and Katherine Newbegin (2011); Facebook: Images of People in Photographs from the Permanent Collection (2008); and Utopian Mirage: Social Metaphors in Contemporary Photography and Film (2007). Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument is the latest in this distinguished line of photography shows at the Art Center.